Uncategorized

How ‘Alfred’ the whale lost its teeth to become a giant filter feeder – The Conversation

Post doctoral research fellow in evolutionary biology, Monash University

Adjunct Research Associate, Monash University

Monash University

Felix Marx receives funding from a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Global Postdoctoral fellowship (656010/ MYSTICETI). He is affiliated with the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels, Belgium; Monash University, Melbourne, Australia; and Museums Victoria, Melbourne, Australia.

David Hocking receives funding from an Australian Research Council Linkage Project (LP150100403). He is affiliated with Monash University and Museums Victoria, Melbourne, Australia.

Travis Park receives funding from an Australian Postgraduate Award. He is affiliated with Museums Victoria, Melbourne Australia.

Monash University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

https://doi.org/10.64628/AA.6tydukgap

Share article

Print article

Baleen whales, such as the gigantic 30m-long blue whale, are the largest animals that have ever lived on this planet. They even beat the largest of the dinosaurs. But, ironically, the secret to their success lies in their taste for tiny prey.

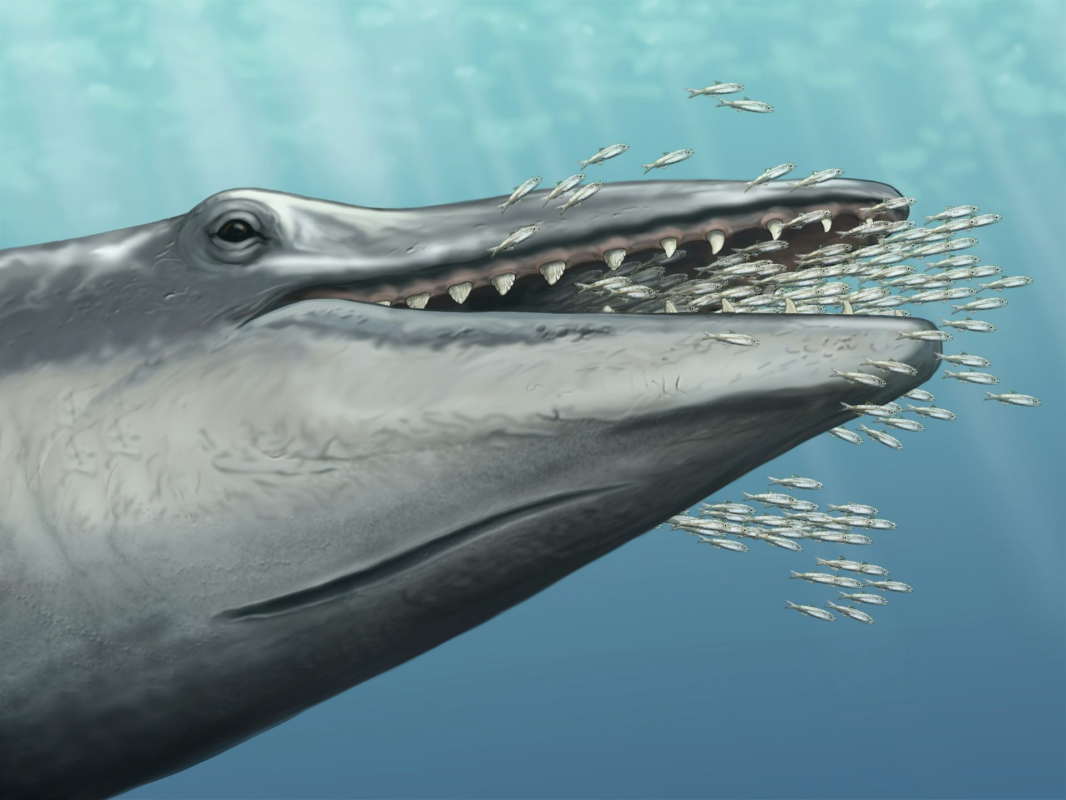

Living whales feed by filtering vast numbers of small fish and krill directly from seawater. This is a rather clever strategy that allows them to cut out predatory middle men and feast directly on the abundance at the bottom of the food chain.

Modern whales are toothless and so capture their prey using their hallmark adaptation: baleen, a series of horny filtering combs that line the upper jaw. Baleen is the key feature that allowed whales to grow big.

From the time baleen first appeared, most whales grew to body lengths of four to eight metres and, ultimately, became the ocean giants we know today.

How and why baleen evolved is one of the greatest mysteries of marine mammal evolution, with even Charles Darwin himself speculating upon its beginnings in his On the Origin of Species.

Like all mammals, whales originally had teeth, which they used to capture and cut up large prey. Previously, it had been thought that baleen evolved alongside teeth in a transitional group of fossil whales known as aetiocetids.

But this idea presents a major problem. How could hard, slicing teeth and comparatively soft baleen occupy the same space in the jaw, and yet not get in each other’s way? Why did the teeth not damage the baleen every time an early whale closed its mouth?

A 25 million year old fossil whale seems to provide the answer, according to research published in the Memoirs of Museum Victoria this week by a team of palaeontologists at Museums Victoria and Monash University (including Erich Fitzgerald, Alistair Evans, Tim Ziegler and ourselves).

The new specimen has not yet been scientifically named, and so for now we simply called him Alfred.

Alfred is an aetiocetid and thus lived during the pivotal time when baleen is thought to have first appeared. But, unlike other aetiocetids, Alfred preserves something incredibly rare: direct, clear evidence of behaviour.

The inner surfaces of Alfred’s teeth are carved out and bear numerous polished horizontal scratches. These marks could only have been made by food and abrasive particles, such as sediment, rushing past the teeth and slowly grinding them down from the inside.

Crucially, the degree of abrasion is so pronounced that the teeth could not have been shielded by adjacent baleen. Contrary to what had been thought, it seems that baleen simply had not yet evolved in aetiocetids.

The horizontal orientation of the scratches suggests that prey was not captured by biting with the teeth, as in the ancestors of whales, but rather sucked into the mouth via a sudden retraction of the tongue.

Suction feeding is common among living marine mammals, including seals, dolphins and toothed whales, who use it either to capture prey or to prevent it from floating away while they swallow. But, so far, suction had rarely been directly implicated in whale evolution.

Suction profoundly affected the way whales fed. Living suction feeders, such as sperm whales, beaked whales and the narwhal, no longer use their teeth to capture prey, and generally have either reduced them or even lost them altogether.

We think that something similar happened in early whales, along the lineage that gave rise to the living species. At the same time, suction freed whales from the need to grasp individual fish and allowed them to target smaller prey.

In turn, this meant that for the first time whales were able to capture more than one prey item at once. This was the beginning of modern whale bulk feeding.

But there was one last problem that whales had to solve: how best to get rid of the water sucked in along with the prey?

Swallowing all of it is obviously unfeasible, so an efficient way of expelling water, but not prey, from the mouth had to be found.

An elaboration of the (by now largely toothless) gums into hair-like baleen provided the answer. In the whales that followed Alfred and other aetiocetids, baleen evolved directly from the gums and voilà, modern whales were born.

By this stage, Alfred and his fellow aetiocetids were no longer part of the grand story of whale evolution. Their lineage had been reduced to a mere sideline, doomed to eventual extinction.

Nevertheless, it is exceptional fossils like Alfred that provide real insights into what early whales were like, where they came from and where they would be going.

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 216,000 academics and researchers from 5,386 institutions.

Register now

Copyright © 2010–2025, The Conversation US, Inc.